Introduction / TLDR

The 2007 recession and global pandemic precipitated major socioeconomic shifts impacting the banking and financial services industry. A wave of branch closures and a shift to digital banking has left vulnerable neighborhoods and populations in banking desert zones without access to basic financial services. At the same time, banks face a loyalty crisis as younger populations in particular move fluidly between competing digital apps, adding and dropping accounts as needed with near zero switching costs.

The Capital One Café demonstrates a radical opportunity to reassert important social factors in banking outside of typical teller or financial advisor relationships and generate deeper loyalty from banking customers. I propose that central to the success of this concept is the possibility of creating a “third space” that provides a hub for community, socialization, and work. The model of physical spaces as conduits for loyalty in financial services is examined and evidence from direct observation as well as a social media analysis of 500 tweets mentioning the Capital One Cafe is presented.

Download the full report as a PDF

(Bibliography is also available in PDF version)

Banking Desertification in the United States of America

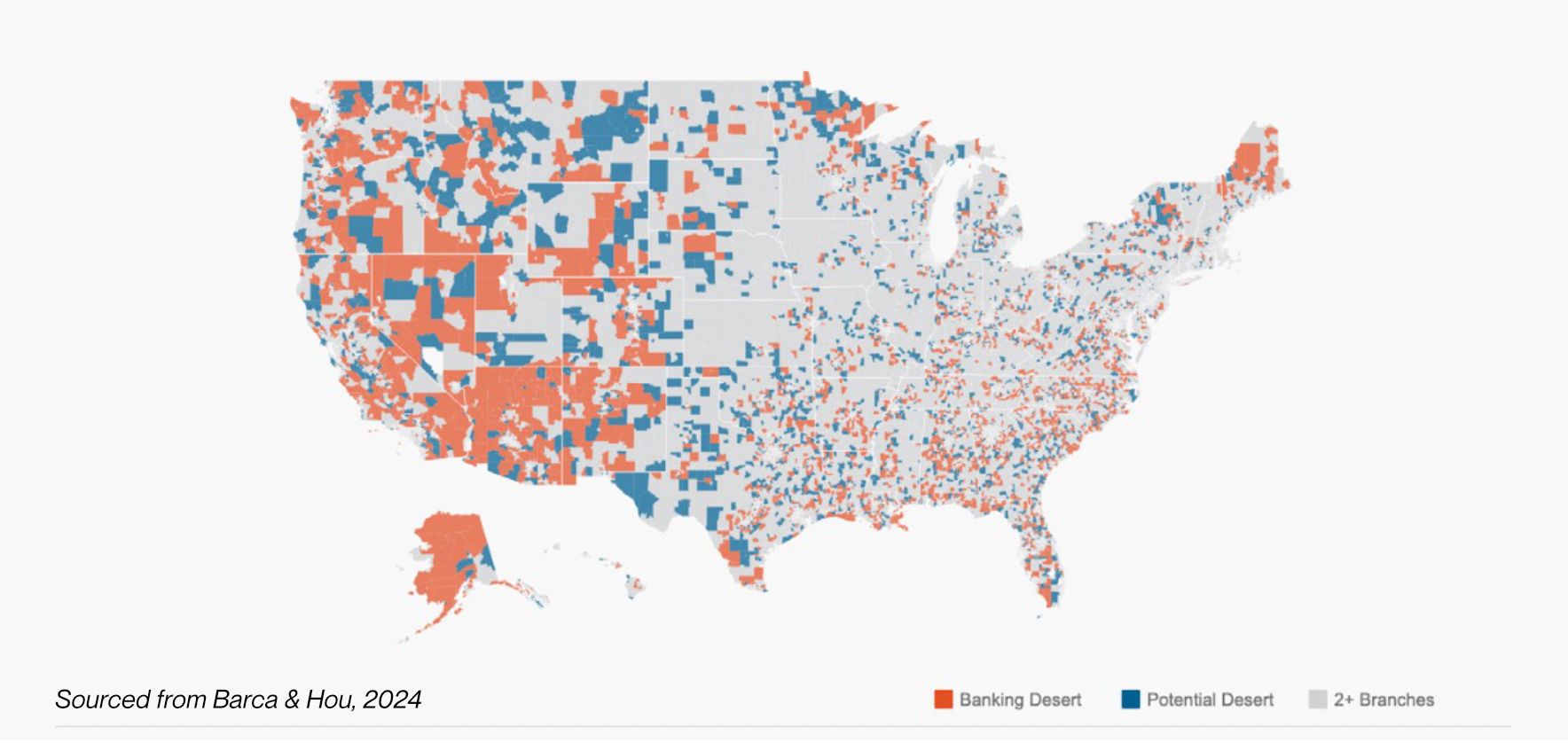

Waves of branch closures in recent years have been disproportionately represented by large financial institutions - those with 10 billion dollars or more in holdings (Cerulli, 2025). These larger institutions have seen more than a ten percent decline in open branches from 2019 to 2023. The closing of many branches has created banking desert zones, which are defined as surveyed tracts that have zero banks within a defined radius from the center. The length of the radius is dependent on the population density. In urban zones banks are expected to be more densely packed, thus the definition of a desert is less forgiving and uses a shorter cutoff radius than in rural areas. Access to fewer bank locations has pushed many users to conduct their banking online, but in a 2024 report as many as 39% of those in desert zones also had limited broadband access (Barca & Hou, 2024).

In addition to reducing bank access for users, branch closures result in a loss of “soft-data” from surrounding neighborhoods. Banking lenders that hold personal relationships with users and ties to the neighborhoods they work in are more likely to approve loans and offer favorable rates to their clients (Morgan, et al., 2016). When institutions lose these personal connections lending drops, particularly in lower- and middle-income neighborhoods. A study on this “soft information” effect found that when lending decreased following branch closures, “the contraction in small business lending persisted even after a new branch opened,” suggesting that loss of soft-data has longer term effects even when a new branch begins operating (Morgan, et al., 2016).

The Community Reinvestment Act & The Origins of Capital One Café

The opening and closing of bank branches has been highly regulated since the passage of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) in 1977. This act was originally intended to prevent redlining by creating oversight and benchmarks for distribution of branches between lower-, middle-, and high-income areas (Ding & Reid, 2020). More recently this law has been criticized as potentially hindering bank expansion, since banks are hesitant to risk opening branches in uncertain locations with additional red tape and costs involved (Feldstein, 2025).

Prior to the launch of Capital One Café, ING Direct USA, a Dutch subsidiary, opened some of the original banking cafés, declaring that “saving money should be as simple as having a cup of coffee” (ING, 2009). Though denied by ING Direct, consumer advocacy groups speculated that the original ING cafés were started as a strategy to circumvent the CRA by operating as “offices”, allowing ING to increase their service footprint in wealthy Silicon Valley neighborhoods without counting against CRA audited branch service ratios.

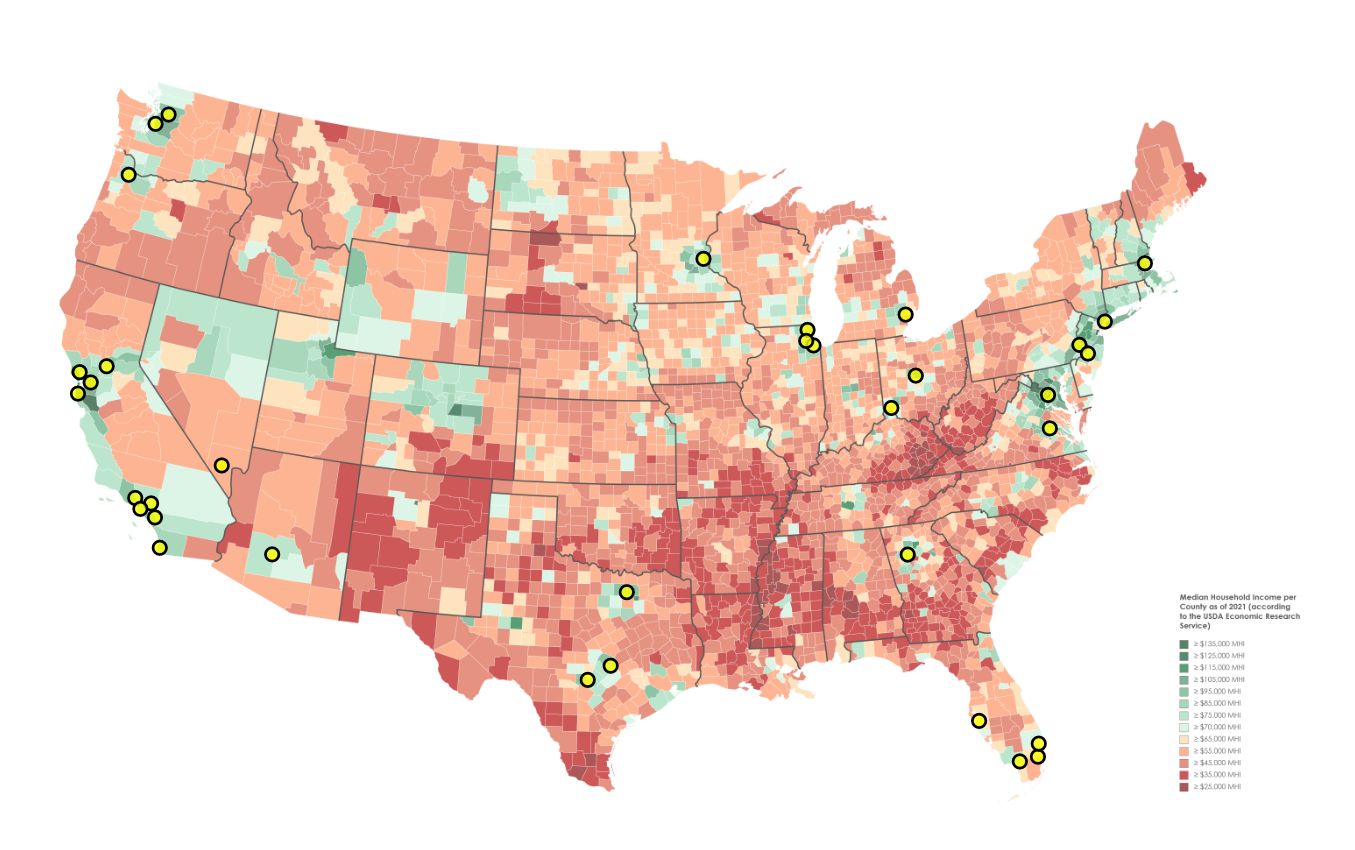

Capital One acquired ING Direct USA in a $9.0 billion dollar deal finalized in 2012, kickstarting their own café banking venture (ING, 2011). Capital One Café now dominates the “café-banking” space with over 50 locations across the United States. Somewhat ironically, Capital One has used their café venture as a pillar in their compliance plan for community outreach and support (Business Wire, 2024). Current café locations, however, still tend to be located around wealth centers.

Certainly, as a business venture, Capital One Café seems to be successful initiative, but to determine whether it is successfully addressing social and financial shifts from the last decade a closer look at how the spaces are used and perceived by customers is needed. To begin investigating, I visited the Capital One Café in the Southport neighborhood of Chicago to observe the space and usage patterns among patrons.

Observations at Capital One Café – Southport, Chicago, IL

The most striking initial impression upon walking into the Southport Capital One Café is the bright, modern, and airy atmosphere. The building is located on a bustling corner, and two-story wrap-around windows fill the main seating area with natural light. As you move deeper into the large building, copious recessed LED lighting and bright white walls carry the brightly lit atmosphere throughout the space.

As people enter, they are greeted by Capital One “Ambassadors” who have a central open service kiosk reminiscent of the service desks at an Apple store. At this kiosk there are takeaway pamphlets highlighting benefits of Capital One Credit cards and during my visit, they were also handing out free luggage tags (highlighting travel perks) to anyone who comes through.

The ambassadors converse informally with passing patrons, and do not stay anchored to the kiosk. During my visit, several people entered the café with their dogs, prompting the ambassadors to approach, chat about the dog’s breed, pet the dog, and offer up treats. Several families with young children also visited the café and the ambassadors supplied coloring pencils and paper as well as some small toys and games. The ambassadors also appeared to know some of the regulars and had extended conversations with two different couples unrelated to banking.

Most visitors moved directly past the ambassador kiosk with a nod or wave and continued to the coffee counter. The coffee area operates just as a normal coffeeshop would, with the exception that every customer is asked at checkout if they will be paying with a Capital One card. If so, their bill is discounted by fifty percent.

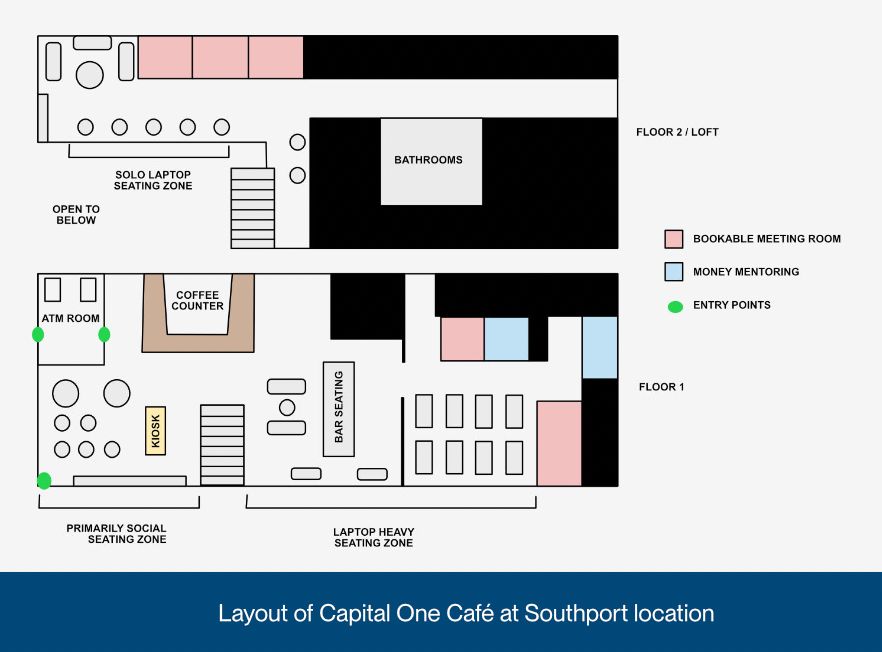

The main lobby area (where the kiosk also resides) was the primary zone for people in groups socializing. I was surprised by how long some of the parties stayed and chatted, including a group of four and a family with a small child that were present for the duration of my hour and a half visit. Upstairs, a wrap-around loft is filled with smaller two person tables. Most people who came alone proceeded upstairs and chose these tables to work on their laptops.

Further back, there is a variety of seating, including padded booth nooks, communal bar style seating (with lots of outlets built in), and more office-style tables at the very back, suited for four to six people. These areas tended to be more laptop heavy as well.

A noteworthy phenomenon I observed was the frequency of visitors in large groups with four or more people. The seating capacity at Capital One Café differentiates it from any of the other coffee shops in the neighborhood. A Starbucks is two blocks away but has a fraction of the seating, even when compared to the downstairs portion of the Capital One Café alone. There are also several popular local coffeeshops nearby to choose from, but these have even less space available – only able to support one or two larger groups with seating primarily designed for individuals or couples. I would gauge that the Capital One Café hovered at about 75% occupancy during my visit. Despite the frequent medium and large parties coming through, plus patrons staying for longer durations than I initially expected, availability of seating was never an issue.

Perceptions of Capital One Café Online

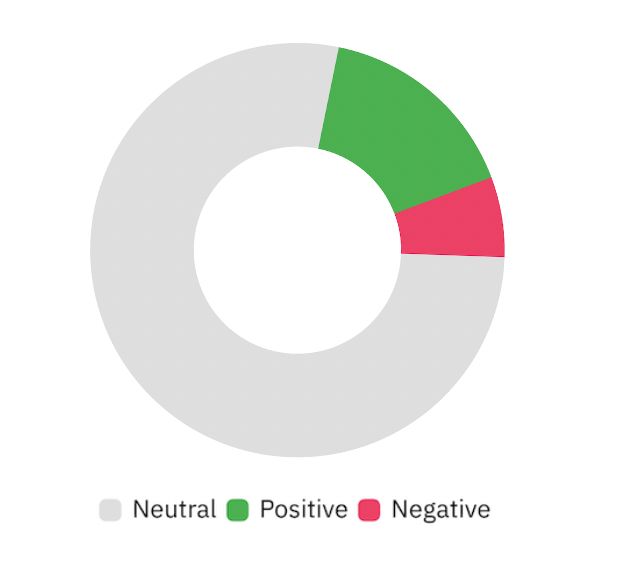

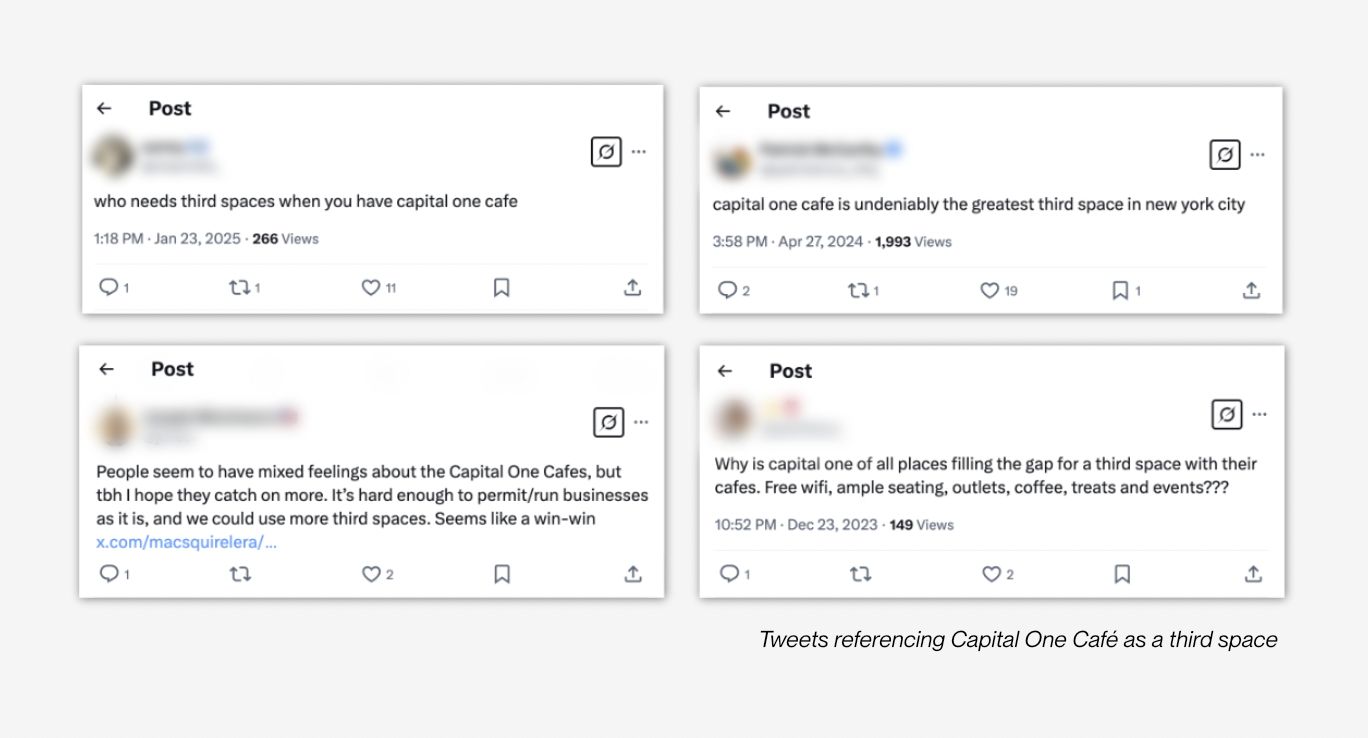

Visiting the Capital One Café made it clear that the space successfully fulfilled needs for both socialization and work, and I was curious how this may have been reflected online. I collected ~475 tweets from X mentioning the Capital One Café over the last two years to conduct an analysis of the discourse and sentiment surrounding Capital One Cafés in the online space.

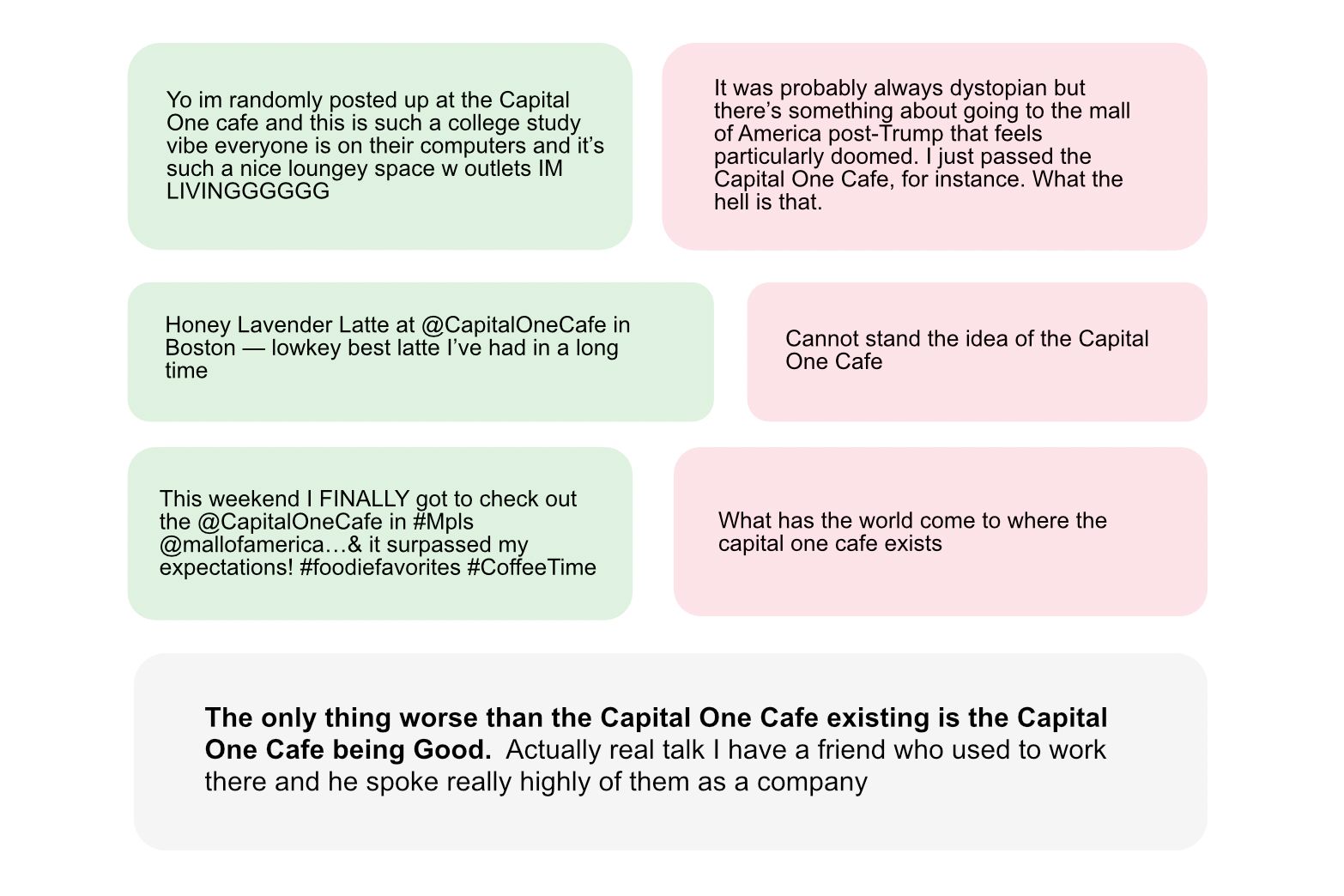

To begin, I conducted a basic sentiment analysis, which indicated a positive lean, though not strongly. Qualitatively looking through the text, negative sentiment tended to be around Capital One Café as a concept, while positive sentiments instead were more often referring to actual experiences inside the café.

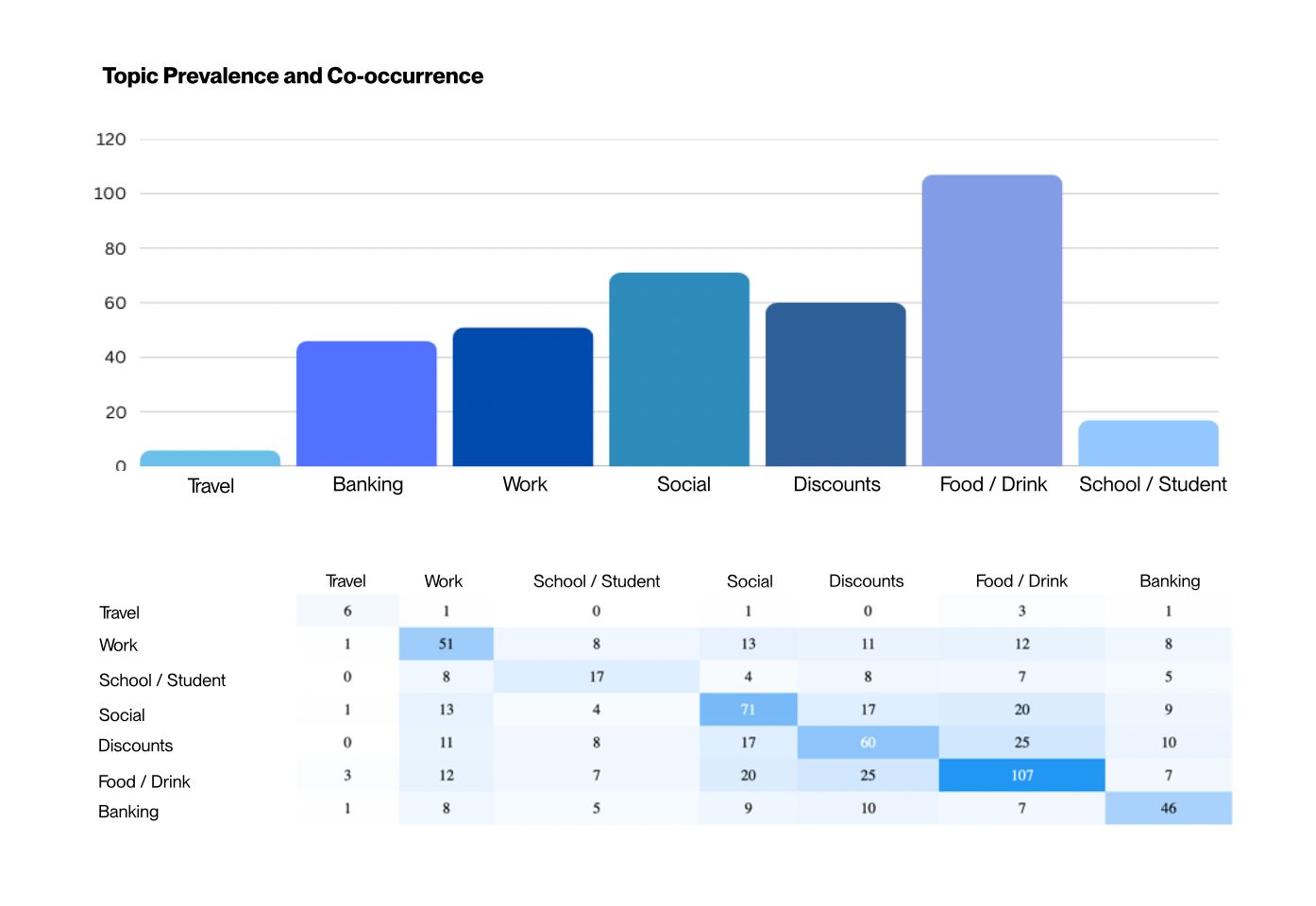

Next, I ran a topic analysis on the data pulled from X with buckets for the following themes: travel, work, school/student, social, discounts, food/drink, and banking.

The well-distributed spread of topic frequency, especially between work, social, and banking, reflects the multi-functionality of Capital One Café spaces. Though still certainly part of the discourse, banking discussions take a backseat to more café-coded topics in the online sphere.

Digital Banking and Loyalty

As the majority of day-to-day financial transactions have moved to apps and online portals and away from face-to-face interactions at branches, banks have seen a marked decline in loyalty. A study by Accenture found that younger generations are much more likely to use multiple institutions or change between institutions when opening accounts (Winch, 2013). Modern customers still seek a long-term financial partner, but have felt abandoned by banks, first from the fallout of the great recession, and also from impersonal app-based services with a lack of human connection (Gronemann, et al., 2023).

The desire for human connection in services, financial and beyond, is particularly acute in younger generations. Generation Z reports the highest levels of both stress and loneliness of any generation – with 79% reporting feeling lonely, and 90% reporting physical or emotional symptoms from stress within the past month (Hathaway & O'Shields, 2022). Generation Z actively seeks out social support-based services and experiences that deliver a sense of community and belonging. The Capital One Café concept is uniquely positioned to fill this need, by prioritizing space and community while maintaining transactional banking operations quietly in the background as a convenience.

Third Spaces and Capital One Café

The concept of a “third space” is often described as a “home away from home” and typically is a multi-functional space that fills a variety of needs for a society or surrounding neighborhood. Third spaces tend to be establishments like local coffee shops, bars, pubs, and community centers. It is well established that the presence of these third spaces positively correlates with quality of life for those in the surrounding community (Jeffres et al., 2009). It is less well-defined exactly why certain multi-functional community spaces play a key role for patrons, and how these places elevate themselves beyond the role of a traditional business establishment.

Certainly third spaces address desires for socialization, but a larger case is presented in Patel’s work on architecture and urban planning. He argues that as we move from work to home we encounter temporal/spatial dissonance when work rhythms bleed into the physical space of home and vice versa. This dissonance emerges from the encodings of physical spaces conflicting with the rhythm of our mental activities. In this model, third spaces act as a physical nexus where our temporal life rhythms intersect and can merge. These spaces between our established rhythmic nodes provide an essential buffer or mental recovery zone that reduces the noise and dissonance of our daily routine (Patel, 2012).

I propose that Capital One Café extends this concept of a spatial-temporal buffer zone by itself existing as a nexus between social, work, and financial functionality. Through its own internal contradiction of space it exhibits no strong “encoding” or “cadence” on those within it, allowing guests to fully exist within their own present rhythm without experiencing Patel’s spatial-temporal dissonance. This may partially explain the dichotomy of reactions between patrons and outsiders. From the outside, the spatial dissonance of a bank and café fusion can be off-putting, but for those on the inside the seemingly contradictory functions provide a neutralizing effect that allows patrons to impose their own encodings on the space.

Urban Design of Third Spaces

To further understand what separates a traditional establishment from a third space, Mehta and Bosson propose a framework of four physical criteria for urban designers that tend to be present in community-viewed third spaces:

Personalization of the establishment

Permeability of the business front

Seating options

Shelter provided

The Southport location of Capital One Café exhibits a great example of balancing shelter and permeability. Floor to ceiling glass lets light into the main lobby, while the bookable nooks and communal work style tables sit sheltered toward the back of the café. This divide also tended to foster the distinct social and working zones observed at this location.

Seating is cited as perhaps the most important of these criteria in supporting social behavior and retaining community in third places. Availability, variety, and comfort in seating arrangements encourage flexible use (Mehta & Bosson, 2010). Capital One Café excels in this area, providing nooks with lounge chairs and couches, large conference room style seating, community bar seating, and traditional two, four, and six-top tables. The copious seating options encourage the patronage of larger groups that may otherwise be apprehensive about finding a space to sit together in smaller café-style establishments.

The sterility of business front stands out as the primary third place violation when examining the Capital One Café within Mehta and Bosson’s framework. Further efforts to personalize and de-bank the outer facades could create a more inviting atmosphere for the outside viewer. Once again, the outer violations may contribute to the distinct differences in sentiment among outsiders and patrons.

Evolution of Place

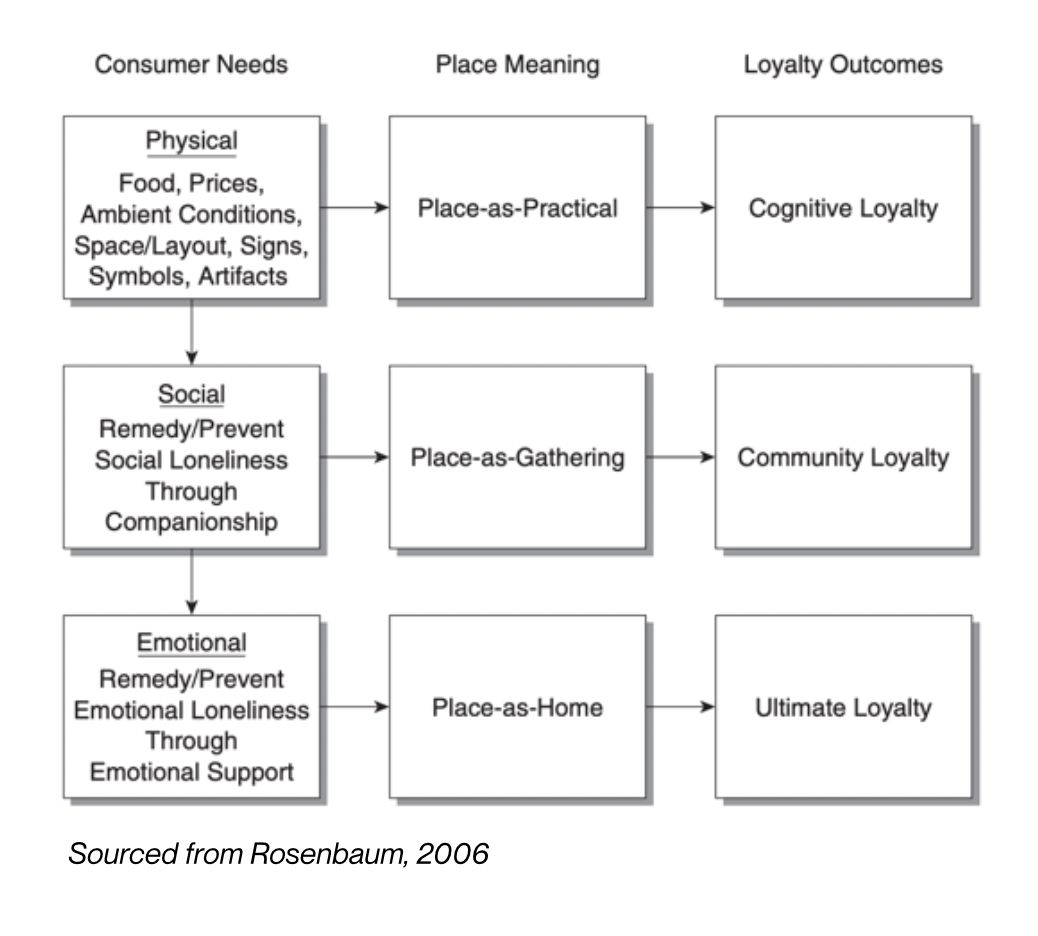

Beyond the elements of urban design that Mehta and Bosson point to as correlated with third places, Rosenbaum models a three-stage model to evaluate the evolution of place from a needs-based perspective:

Physical consumer needs, many of which relate to Bosson’s urban design factors, provide a baseline for a “practical” business that meets community needs. Capital One Cafés build on this with amenities like high-speed internet access and access to ATMs.

To advance to the level of community loyalty, customers social needs must be addressed as well. Capital One Café’s ambassador program, spatial features, and meetups lay the groundwork for addressing these needs and thus support an evolution towards a “Place-as-Gathering” (Rosenbaum, 2006). During my Southport observation, ambassadors had several extended chats with visitors, including some that appeared to be regulars. Café features are also set up to facilitate socialization, from (corporate branded) games like Connect Four, checkers, and chess in the lounge spaces, to the communal bar-style seating options.

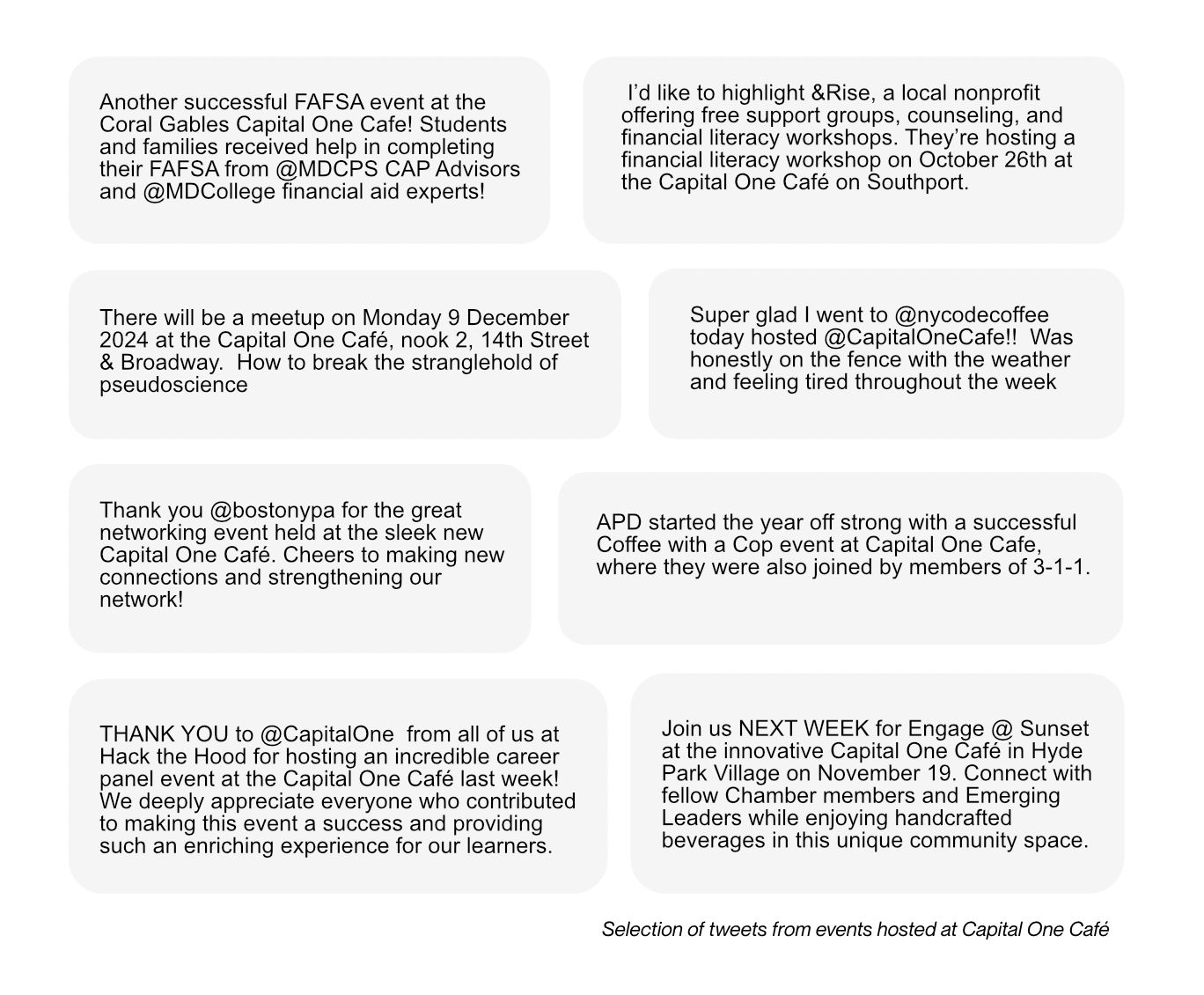

The massive floorplan of most Capital One Café locations compared to typical coffee shops also enables larger gatherings like book-readings, workshops, and affinity-meetup groups (see above for example events from collected tweets). Chicago Code, a group for developers, meets at the Capital One Café in downtown Chicago and regularly hosts over 200 people. Capital One not only has the space to accommodate with a full floor reserved for this event, but also provides free pastries and a free coffee for all attendees. Community loyalty is established through these meet-ups that engage remote workers, freelancers, students, and recent transplants to the city looking for meaningful connections.

To advance the meaning of a place to “Place-as-Home” through emotional connection is the pinnacle of relational third place theory, and consequently ultimate customer loyalty. This step requires adequate provisions for the previously mentioned social and practical needs, multiplied over time to allow the evolution of strong personal bonds. (Rosenbaum 2006).

The Money and Life Program from Capital One

Capital One’s Money and Life mentoring program seems well-suited to foster deeper personal connection with members. The program consists of three initial sessions with a Capital One “ambassador” or “mentor.” These sessions are free for both Capital One customers and the general public, and are a perfect example of a social support-oriented program. I signed up for a session to see how the program worked and to learn more about how these sessions are designed.

The primary focus of the session revolved around identifying core life values, ranking how they are currently represented in one’s life, and then creating actionable steps with concrete due dates to help improve these rankings and shift the participant’s life towards alignment with their core values. The experience overall feels much more akin to life coaching than a typical appointment with a branch agent. While discussing the experience with my mentor as a debrief, she stated that the idea behind the program is to help people “bring clarity to their own life and goals.” To this end, mentors do not provide any financial advice. Instead, the mentors facilitate structured thinking about a participant’s life and goals and help distill these into action items.

The worksheet with the values and goals, as captured by the mentor, is shared at the end of the session with the participant. Calendar invites for the due dates of each identified goal are included as well. When scheduling subsequent mentoring sessions, the availability calendar automatically filters by your mentor’s availability. You can opt to change mentors, but Capital One nudges users towards longer-term relationships with their Money and Life mentors.

Beyond the Bank

From a theoretical perspective, Capital One Café is well-positioned as a third space, but more importantly, social data reveals that locations have in fact already begun to fill this need for patrons.

It is unimaginable that sentiments like this would exist for a traditional bank branch location. Though cafés may seem like a random and unlikely venture for a bank, expanding into social place-making is an opportunity to meet the needs of customers across industries and beyond the confines of any typical or historical business model.

Conclusion

The trend of banking branch closures shows no sign of letting up. Initial opportunities to differentiate through frictionless app experiences has given way to financial fragmentation, with users splitting their banking between several institutions, particularly those in younger generations. Social support and community through placemaking may represent a new opportunity for lasting customer loyalty. Capital One Café has created a tremendous advantage by filling a deep need for third spaces in communities. Other financial institutions would do well to explore ways of leveraging design of space to foster long term customer partnerships and connections.